The Pleasure Principle

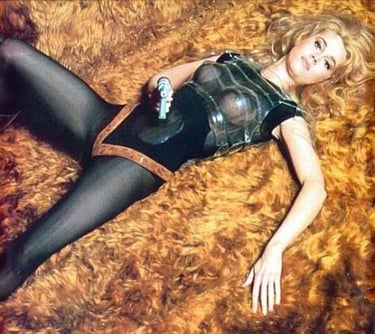

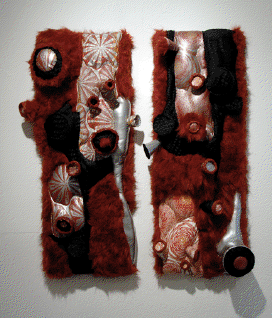

Gretchen Jankowski is currently engaged in constructing mixed-media wall panels using an imaginative mixture of nontraditional materials with alternative printing and sculpting methods. These abstract panels have the distinct “Groovy, baby!” look of 60s and 70s furniture, decor, and fashion—a look characterized by vivid colors and shapes, a profusion of surface design, and a variety of textures including tactile materials such as furs and shags. As a quick way to describe Jankowski’s wall panels to the uninitiated, I have often said that if Barbarella were to marry Austin Powers, this is what their living room decor would look like.

In Barbarella, we find ourselves in the year 40,000, a time when humans are so advanced that they no longer need to have sexual intercourse, which was long ago proven to be “too distracting.” Instead, compatible partners each take a special pill and, touching hands, are able to reach perfect sexual fulfillment with one another. Barbarella, however, has a chance to sample the old-fashioned way of doing things when she is sent on a mission to some less civilized galaxies. The first man she meets, covered all in furs, makes love to her in his fur-lined carriage. She then dons, courtesy of her lover, an utterly fabulous outfit made out of an assortment of wild furs. In the rest of the movie, futuristic metallic fashions are the norm. These simply don’t invite touch, or remind one of pleasure and abandon. However, Jankowski’s wall panels do.

From the moment you lay eyes on their concatenation of shameless furs, alluring crevices, and surprising protrusions, you want to reach out and run your hands along their curves and inside their holes. You want to stroke all of their surfaces, find out how they feel, speculate as to what they are made of, delight in how soft or hard they are. Jankowski’s work is unabashedly about pleasure, both visual and tactile. The artist has insisted that viewers should touch the work, to experience it firsthand, to leave their imprints. She is not at all precious about the objects; she makes every inch of them by hand, and a reciprocal engagement of the objects with the viewer is something that she does not mind, even delights in. Much like the distracting, old-fashioned way of achieving sexual union in Barbarella’s world, an involvement with Jankowski’s work is joyously participatory. When regarded in the context of the strictly hands-off (and very square) museum world, it is downright promiscuous.