The Innate Qualities of Instruments

The Cellist (1913) by Anton Guilio Bragaglia

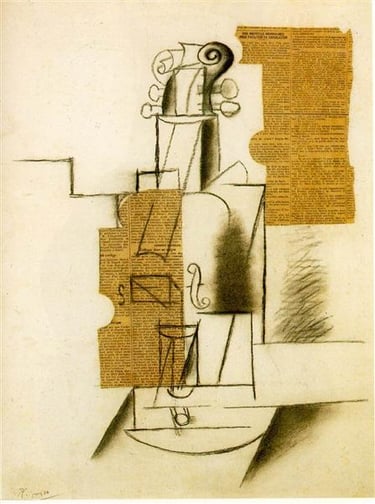

Violin (1912) by Pablo Picasso

Photograph of virtuoso Glenn Gould playing Bach’s Goldberg Variations

The piano, cello, and violin have all evolved in their usage, design, and function. What would be seen as controversial usage decades ago is now common practice. It is for this reason that it has become an increasingly complex matter to determine what the characteristic usage of these instruments would be. Nevertheless, given a basic analysis of form, range, and texture, one can observe the fundamental capacities of these three instruments. By looking at Erik Satie’s Gynompédie No 1, the Elgar Cello Concerto in E minor (opus 85, 1st movement, Adagio Moderato), and Johann Sebastian Bach’s Concerto in A Minor for Violin (Allegro Assai), we will see how the piano, cello, and violin have been used characteristically.

Erik Satie’s Gynompédie No. 1 illuminates the piano’s ability to play both melodies and chords simultaneously. The piece begins with a bass note followed by two triads played in the middle register. In a beautifully simplistic manner, the melody begins in the higher register, using a soft dynamic (appropriately called piano because of the instrument's ability to play soft and contemplative melodies). The texture of the higher register of the piano has the ability to glisten, like droplets of rain. Satie also takes advantage of the piano’s distinctive black and white notes, constructing his chords frequently with black notes and his melody with white. The interchanging of both produces a stable form, like a journey at sea. Moreover, Satie’s usage of bass notes and a higher register melody is typical of a piano composition because of how the pianist's hands naturally position itself on the instrument. Here, therefore, the piano is used typically, using chord constructions plus a melody as the underlying structure of the composition, while bringing out the piano’s innate ability to produce a soft, glittering texture in the higher register. The piano contributes to the meaning of the work in that it becomes a contemplative and romantic sounding work, indicative of a love story.

The first movement of the Elgar Cello Concerto showcases the cello as an emotive instrument, able to sound like the cries of the human voice. The vibrato of the cello is distinctively warm and rich; the way in which one bows the instrument is much like the dynamics of a singer. Yet like the piano, the cello does not require breath, which allows it to play long legato melodies that ascend to the highest register back down to the lowest. The beginning of the composition makes use of the frog, producing crisp and intense lower chords that use the natural curvature of the cello’s bridge to play a bass note followed by a forte double stop. By the middle of the piece the orchestra responds loudly and passionately to the cries of the cello’s tessitura. The quality of this sound literally makes one want to cry. Here, one can see through the use of the cello’s warm vibrato coupled with its passionate tessitura, how Elgar takes advantage of the innate texture of the instrument. The symbolism is heightened by the cello because of its ability to sound like the cries of the human voice, thereby producing an underlying narrative of death or loss.

Smaller than the cello, the violin is also less resonant, which is the reason why several violins are being used in Bach’s Concerto in A Minor (BMV 1041, Allegro Assai) to cut through the sound of the accompanying strings. Yet like the cello, the violin does not require breath, which is perfect for Bach’s Concerto in A Minor (BMV 1041, Allegro Assai), which seems to chromatically progress without end. The violin also has the ability to do fast embellishment, using trills and appoggiatura with little sweat. This piece also uses the violin’s node, or its harmonics, creating a glassy texture. Like the cello, the violin can play the arco and pizzicato dynamic, while also controlling its vibrato by means of frequency modulation. The legato lines of the arco are used here to create a heavenly experience, while the interchanging between non-vibrato and con-vibrato heightens portions of resolution in the composition. The violin’s naturally high register contributes to the heavenly quality of this work, as if speaking to God, as perhaps Bach would have intended.

As we have seen, the piano, cello, and violin all have an intrinsic texture and range. Each of these compositions would not have the same effect and meaning if played by another instrument. Erik Satie’s piece, for instance, would not be physically able to be played by violin or cello, and the intense passion of the Elgar Cello Concerto would be muted if played by the piano or violin. Each of these compositions bring out the innately characteristic qualities of these instruments.