Pietro Germi's Seduced and Abandoned

The Object of Gaze: the Object of Desire

Vincenzo Ascalone governs his family with the patriarchal right that is only traditional in 1960s Sicily. When his 16 year-old daughter, Agnese Ascalone is seduced by her sister’s fiancé, her father immediately demands that the man, Peppino Califano, marry his daughter, and antics ensue. The film is a dark satire of Sicilian social customs, rape, marriage, and honor laws.

In considering the power relations between men and women–the way in which men gaze at women and, by consequence, how women see themselves, a certain understanding between the observer and the observed materializes into basic Feminist theory. The Male Gaze is a concept of asymmetrical power: forcing the viewer to regard the action from the perspective of a heterosexual man, denying women human agency, objectifying them – giving the beholder a striking sense of superiority. A fixation on women from a masculine standpoint characterizes the movements of the camera in Pietro Germi’s Seduced and Abandoned (1964). In its often seductive approach, the camera’s agility allows for distinct insight, conveying the archetypal and patriarchal Sicilian state of mind.

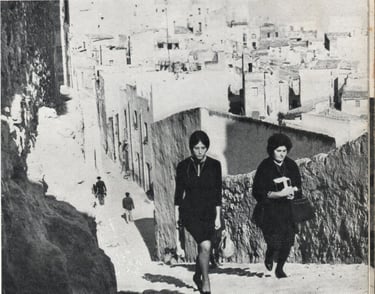

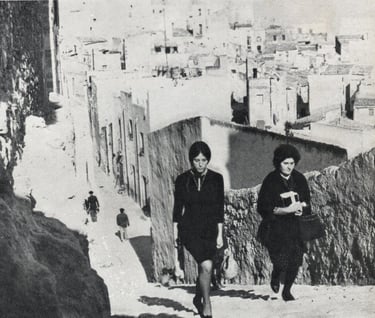

Opening the film, the camera follows two women walking silently through a typical Sicilian town. Its relation to the women begins neutrally, uninvolved in its pursuit. The interaction then evolves and takes on the persona of a watchful townsperson, scrutinizing the protagonist Agnese and her accompanying servant Consolata. Stalking them from behind rails, the pan of the camera allows the audience to revel in a slightly more obsessive and sensual approach. Almost abruptly, it assumes an intrusive focus as it closes in on the alluring Agnese, daughter of the prominent Ascalone family. The extreme close-ups become an unreal and intense perspective, so close as to even suggest a breathing-down-the-neck proximity, one of many allusions to the motif of social pressure prevalent throughout the film as enforced by the patriarchal system. The young girl stares at the ground: complacent and cooperative. This excessive and neurotic concentration will typify the masculine temperament that dominates the imminent scenes.

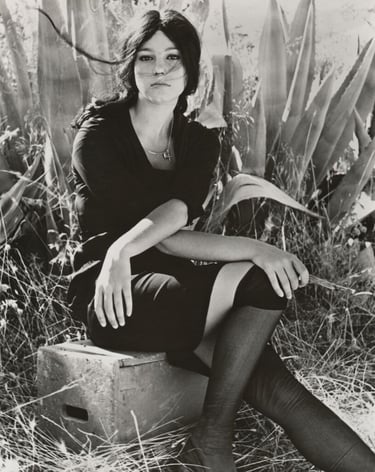

The episode of the actual seduction of Agnese is also distorted in its interpretation. The camera acts as an extension of the exploitive Peppino Califano, her seducer. It approaches her, closes in on her, corners her, and then overwhelms her. She cowers, “lamb-like” as her name suggests. The pressuring advances convey Pino’s carnal lust, making her not only the object of his erotic fantasy, but, vicariously, of ours as well.

In yet another scene, as Agnese reaches the front door to her home, a close-up of the door plaque and her adjacent face puts into focus the tyrannical, patriarchal honor code that so torments her. The plaque bears her family name, and she again looks down with purposeful subordination. In the calculated frame of this subtle comparison, Germi highlights Agnese’s reservation: her shame in respect to her familial duty. It is this male-dominated methodology that smothers her and coerces her into becoming the obedient puppet of her father’s schemes.

Later on, Peppino recounts his skewed version of the succession of events before the town’s magistrate. After his biased confession, both families feud within the judge’s office. The camera zooms in on the diffident and detached Agnese, statically seated and juxtaposed sharply with the excessive commotion of the others. She is distant, tearing silently. By directing our attention to “poor” Agnese, the camera compels us to consider her silence -- a reminder of her suffering. Momentarily, she is not sexualized; however, she is still the object of male scrutiny and thus, victimization.

After news of the family scandal becomes public, the Ascalone family pushes its way through a piazza of a sizable crowd of mocking townspeople. In her ultimate walk of shame, Agnese struggles through the mob of overbearing men, who satirize and ridicule her. The camera acts as one of the crowd members, honing in on her fight against the men, the town, and family pride, in an effort to hold her ground and uphold her self-preservation.