Indonesia, Contemporary

Caitlin Johnson

7/19/2011

I’ve always been a little tongue-tied when it comes to Asian contemporary art. In such a relatively short period of time, the global awareness of an “Asian” art scene has ballooned. Yet, whether it’s the utter tangibility of a lurking art market or the endemic championing of an oft strategic/marketable national identity (“[insert visual effect] = [insert nation]-ness”), I have always had trouble creating a dialogue with much of the art without being distracted by all the noise surrounding it.

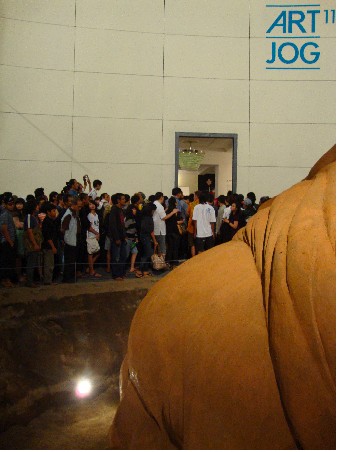

My summer stay in and out of Yogyakarta, Java has offered me ample time for contemplation about Indonesia’s contemporary art story. This past weekend the Jogja Art Fair (ART|JOG|11) opened at Taman Budaya, adjacent to the city’s historic center, now-tourism hub, Malioboro. This marks the fourth year of the artists’ art fair, the second since it changed its name “to become part of the international market.”

Javanese artist Eddi Prabandono was commissioned to create the fair’s annual site-specific work, a giant, sculpted clay baby’s head, modeled and named after his daughter. The sculpture, part of the larger “Luz Series,” takes on a very different connotation at the foot of the entrance to ART|JOG|11. The “big, sleeping baby giant” was more than once used as a metaphor for Indonesian contemporary art during the fair’s inauguration.

The “sleeping” likely references the Indonesian government’s lack of awareness toward its contemporary art while it’s been actively promoting more traditional arts with such projects as the American Batik Design Competition (featuring three $15,000 grand prizes). In the absence of government support, collectors have played the leading role in shaping the contemporary art scene.

A friend broke it down for me: “Try being a famous artist in America. Difficult, right? In Yogya you just need to show your work or organize a show and you can become world renowned.” He went on to explain how all of Western art history was only imported during the last century. In what he described as a place outside art historical space and time, modern and contemporary don’t refer to a historical context, but are rather adopted “styles.” And where these styles can be adopted and replaced, contemporary art exists as a series of instances, seemingly isolated blurbs that simultaneously enter and exit the spatial fabric of global consciousness.

ART|JOG|11 provides a context, stage, and identity for the art, however limited a snapshot it may be. In that respect I understand the need for the fair’s international perspective and all the accompanying hoopla. Yet, the national art fair model still seems to obscure just as much it reveals.