Hip Hop & Holograms

Evan Moffitt

4/30/2012

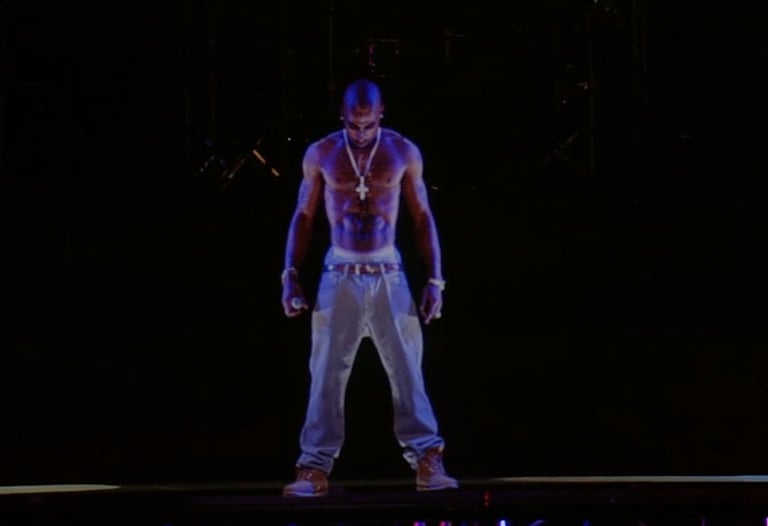

This year’s Coachella festival ended with 75,000 sweaty hands in the air, joined by

another: the ghostly paw of Tupac Shakur, risen from the dead in holographic

glory. Dr. Dre and Snoop Dog, celebrating their 20th anniversary,

brought the late rapper out to join them and a slough of other A-listers (50

Cent, Wiz Khalifa, Warren G, and Eminem).

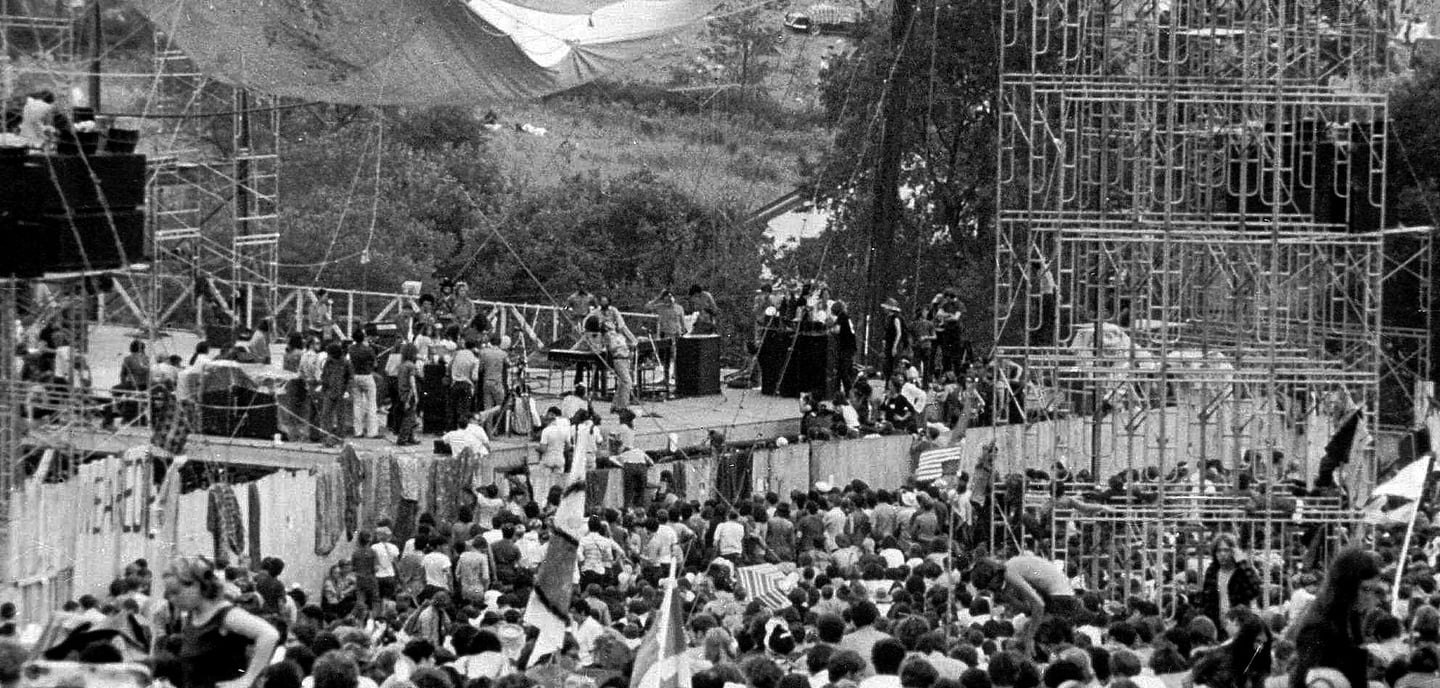

This was the second weekend of Coachella, the notorious repeat event that grabbed

worldwide attention when executives at Goldenvoice, which hosts Coachella,

decided to expand the festival. News of Pac’s hologram had traveled the world

faster than Captain Kirk on the Enterprise; by the time he rose from the stage,

so many people were standing on their tip-toes I could only catch ghostly

glimpses. The pinnacle of a multi-million dollar weekend with a star-studded

lineup was a masterful feat of holographic technology, but it was also a trick

of light and air. A dead (and resurrected) musician, it seemed, was getting

more attention than all of the living acts on the lineup.

The festival—which included Swedish House Mafia, the hit European DJ collective, as

Day One headliner—was engineered for the iPod generation, for a clientele of

festival-goers weaned on 3-D movies. More impressive than the musicianship I

witnessed was the technical production, full of flying LED screens, fire

cannons, and spectral MCs. Modern youth has an insatiable appetite for visual

stimulation, one that Coachella spent its top dollar to satisfy. Yet in

satisfying it, they dwarfed the music at the heart of the festival.

Coachella has grown from a 1993 concert attended by 25,000 to one of America’s biggest

musical events. As I explored the Polo Fields, it became incredibly evident

just how much money was pooling around in that pop-up oasis. The fact that the

festival could sell out two consecutive weekends and pay to keep some of the

music industry’s biggest stars in Southern California for a week is almost as

impressive as the show itself. While I was excited just to be there, I saw

Coachella veterans shaking their heads at a festival they believe is growing

too fast for its own good.