Exercises in Self Discipline: A Review of Matthew Barney's Redoubt

Michelle Kim

5/2/20205 min read

This past February I had the rare, very exciting opportunity to attend a screening of Matthew Barney’s 2019 film Redoubt during the Frieze Art Fair—fellow GRAPHITE Journal staffer Haley Penn and I had spent all day chugging complimentary iced matcha lattes, ogling LED signage cramped next to humongous abstract paintings, and fanning ourselves with cardstock pamphlets. Despite the exhaustion and dehydration, we were eager to finally experience A Matthew Barney Film TM. Many compare viewing Barney’s films to endurance tests, similar to ones that are performed in his Drawing Restraint series. Even the runtimes of his films—the entirety of his Cremaster Cycle series is a whopping 398 minutes—are mental marathons. While Redoubt is a relatively vanilla 134 minutes, audience members slowly trickled out of Paramount Theater throughout the screening.

I’ve been a fan of Barney’s work ever since my freshman college roommate Savannah enthusiastically hung up a Cremaster 3 poster in our dorm. Matthew Barney’s own career began during his time at Yale, blossoming when the faculty were impressed by his installations in the school’s athletic complex. Soon after his graduation in 1989, he participated in a group show that caught the attention of gallerist Clarissa Dalrymple, who introduced the promising young artist to art dealer Barbara Gladstone. In 1991, Barney had his first solo exhibition at Gladstone’s son Stuart Regen’s Regen Projects. Since then, his career has plateaued to a point of constant acclaim— from annual exhibitions at major institutions and regular appearances at biennials.

Redoubt is a modern adaptation of the Roman myth of the hunter Actaeon, whose chance encounter with a flustered bathing Diana (played by renowned long-range shooter Anette Wachter), goddess of the hunt, prompts his eventual demise. Sectioned into six vignettes, referred to as “days of the hunt,” Redoubt is an exercise in tolerance as we helplessly witness the disintegration of a mild-mannered state land manager, referred to as the Engraver (played by Barney sporting heavy SFX makeup), and his seemingly mild-mannered lifestyle in the central Idaho mountains. Despite the typical feature length runtime and use of Tarkovsky-like wide shots—painstakingly put together by commercial director of photography and longtime collaborator Peter Streitmann—Redoubt makes it a continued point to disrupt the conventions of Hollywood filmmaking. Even pre-production decisions, from the use of a micro crew (the film’s choreographer Eleanor Bauer also plays one of Diana’s assistants) to the lack of dialogue, have emphasized Barney’s ardent commitment to his vision.

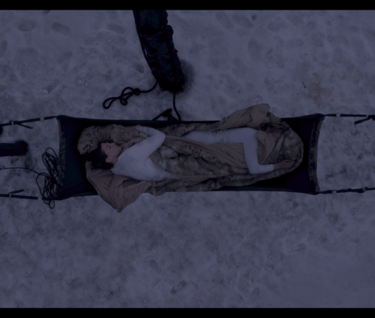

Barney alludes to the visual language of Manifest Destiny-era ideas of romanticizing nature using sublime drone shots, a sarcastic nod to National Geographic documentaries, to depict the game of cat and mouse not only between Actaeon and Diana, but between Actaeon and the land he was hired to protect as well. As Diana’s nymphs effortlessly perform aerial acrobatics on dangling pieces of waterproof nylon, the Engraver struggles to trudge against endless fields of unmarked snow. As Diana and her attendants serve as an allusion to their nonhuman mythological counterparts, Barney’s character reminds us of the innate vulnerability of man. Nature’s true apathy is used as a thematic warning to viewers, that nature is relentless and her punishment unabated, but how can Barney assume that he is not implicated as well? As Redoubt chides its 21st century lackadaisical audience for our irreversible damage to nature, it also chastises starry-eyed, artistically-inclined optimists who fail to fulfill their own creative fantasies. Agonizingly long scenes of Actaeon indulging in his electroplating hobby seem to allude to Barney’s own artistic practice, especially in regards to the meticulous dedication that he invests in all of his projects. Extreme close ups of copper sheets submerging and sparking in vats of fluorescent turquoise chemicals cleverly reference Barney’s admittedly admirable inclination to use enormous chunks of metal and similarly intimidating media. River of Fundament, Barney’s 2014 loose film adaption of Norman Mailer’s Ancient Evenings, also confronts the artist’s questionable carbon footprint. Yet he makes a clear distinction between Barney the artist and his ill-fated Engraver; that while Actaeon is simply a victim of his own naivety, it’s Barney’s responsibility to warn others not to give in to this naivety. Despite Barney’s attempts to efface the cloud of his persona, through the appropriation of Actaeon, he still succumbs to the same habits that have iconicized him. Barney takes on the great aspiration to chastise the complacent—without criticizing the hypocrisy of his own positionality.

During classroom crits, the very rare mention of his name conjures visions of greatness. His practice has become synonymous with pure, raw artistic expression. The sheer hyper masculinity and eroticism of strapping yourself up and catapulting your naked, vulnerable body across white cube gallery walls. The commitment, the viscerality, synonyms of those magnificent words! And with this incomprehensibly high status, of course, it takes a viewer of a certain caliber to digest, let alone appreciate and analyze his work. For the most part, this caliber can only be garnered through a privileged upbringing, one made possible with nepotism and financial stability, to name a few prerequisites.

Barney’s films are iconicized in the art history canon as much as ancient Roman myth has been revered as foundational in the development of storytelling. Redoubt, his most recent work, fails to compel its audience and lacks the shock value that has defined Barney’s previous endeavors. While Barney makes use of incomprehensibly expensive cinematic cameras and similarly impressive shooting equipment, with stunning results nonetheless, the end product becomes too obsessed with its means as opposed to providing a profound thematic takeaway or even a lesson. I’ve always strongly admired Barney’s ability to make whatever he wants, yearning for the full creative control he obsesses over not only in the production of his work, but especially in its presentation and in the rights he holds. He epitomizes the self indulgent artist– one who has no reservations in orchestrating elaborate film productions with beautifully composed montages of the Bronco Stadium and scrap yards gushing with fecal matter– yet through this unrestrained expression he neglects responsibility of the film’s message. His relatively normal Idahoan upbringing and the limited microbudgets set for his films may suggest otherwise—however, the very existence of these budgets and his relatively unchallenging transition into the notoriously discriminatory art world are representative not only of his identity as an artist but also his validity in speaking on social and political issues. It would be reductive to simply render Barney’s work as obsolete due to changing times, but Redoubt’s unconvincing attempt at displaying the repercussions of industrialization is a shame due to Barney’s prodigal amounts of conceptual flex and institution handed checks. It is a simulacra triple threat—as much as Barney’s Idaho mountainscape is a metonym of the American landscape, Los Angeles Frieze is as much of a representation of the bustling international art market as much as the Paramount lots where the fair takes place are supposed to mimic New York City’s street blocks.

The artist’s inclination towards the extreme has given him a rockstar reputation in the contemporary art world, but to what cost when he has become an impression of his own stardom? In the grand scheme, it is perhaps time for us to yield Barney’s celebrity to the multiplicity of newer talent. Despite this realization, at the end of the screening, with a fraction of the audience still remaining, Barney himself came out for a surprise Q&A with Sundance Ignite curator Shari Frilot. Admittedly, Haley and I gasped like fangirls.