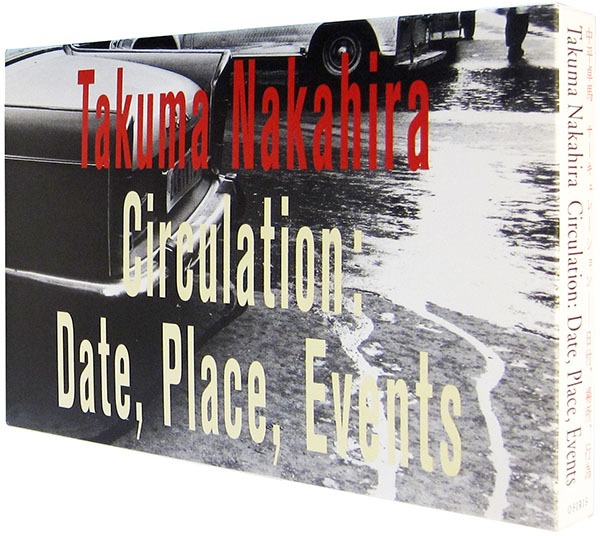

Circulation: Date, Place, Events

Emi Kuriyama

1/29/2013

Influenced by William Klein’s 1956 photobook New York, a community of left-leaning Postwar Japanese photographers employed the are, bure, boke (rough, blurry, out of focus) aesthetic, rallying around their short-lived publication, Provoke. Takuma Nakahira, in particular, was drawn to Klein’s ability to maintain a perpetually moving perspective, dispelling the myth of photography’s ability to capture obscured reality in false totality. Visually, the link between the New York school of photography and Provoke photography is undeniable: their persistent use of available light, black and white photography in the age of color film, blurred nightscapes, skewed angles. The bizarre, blurred, absent gaze of Diane Arbus’ “freaks” reappear in Daido Moriyama’s uncanny photographs of Osaka youths. Both Klein’s and Robert Frank’s photo books seem to have even inspired the format of this generation’s chosen medium; Nakahira alone published several seminal photo books.

However, the aesthetic lineage of Takuma Nakahira and other Provoke photography often distracts Western readings of their work. Exemplified in the text accompanying LACMA’s Daido Moriyama exhibit last spring, curators and scholars too often regard Provoke-era works as a sort of allergic reaction to post-World War II “westernization”. Here, it seems the increasing interest in and exhibition of postwar Japanese photography has come packaged in a vacuum of understanding. In “Photography’s Discursive Spaces”, Rosalind Krauss rails against this disregard for distinctive “discursive spaces”. True to Krauss’ argument, this disregard for alternative Japanese photography as a politicized media produces “incoherence” in these contextually cleansed readings of the work.

Takuma Nakahira’s oeuvre provides the most overt example of the Provoke generation’s political aspirations, especially in the moment of The Seventh Paris Biennale. With the incipient de-politicization of mass media and the silencing of public dissent in the 1950s and 1960s, alternative Japanese photography, including Provoke artists, developed into the creative realization of counter-media, voicing the resistance of the unheard. Grappling with the question of their own Postwar identity, the Japanese public faced issues of censorship and occupation, dehumanization within a high-growth economic recovery, and constant political upheaval.1 These overwhelming societal dilemmas lacked a public mode of discussion as political and corporate powers deliberately trivialized mass media, rendering the public mute.2 In tandem with these invisible societal shifts, the Tokyo Olympics of 1964 prompted rapid construction and “modernization” of the prewar cityscape. Pouring a total of one trillion yen into this construction of a cleansed metropolis, the government’s endeavors paradoxically monumentalized Japan’s re-entry into the international community¬––rejected by the cancellation of the original 1940 Tokyo Olympics in response to Japan’s deepening conflict with China––by completing pre-1945 ambitions, ranging from the bullet train system to the expansion of the sewage system.3 In this context of shifting societal and urban structures, Takuma Nakahira began to publish his essays on film and photography while producing his own photographic work under the guidance of Shomei Tomatsu.

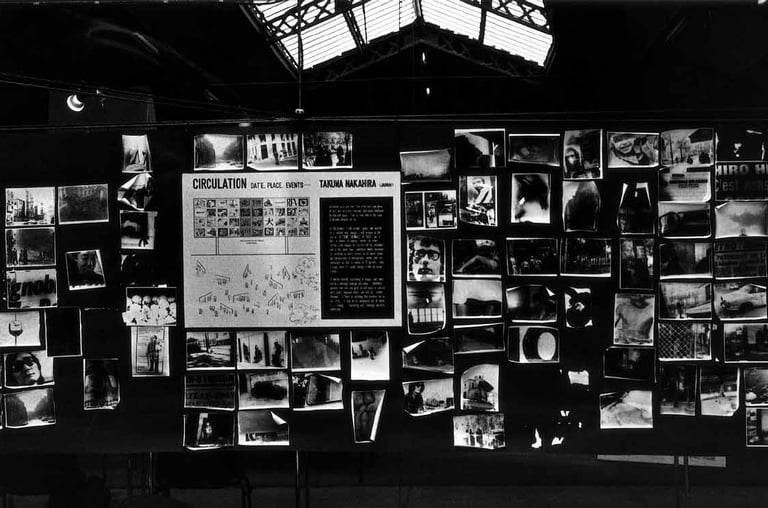

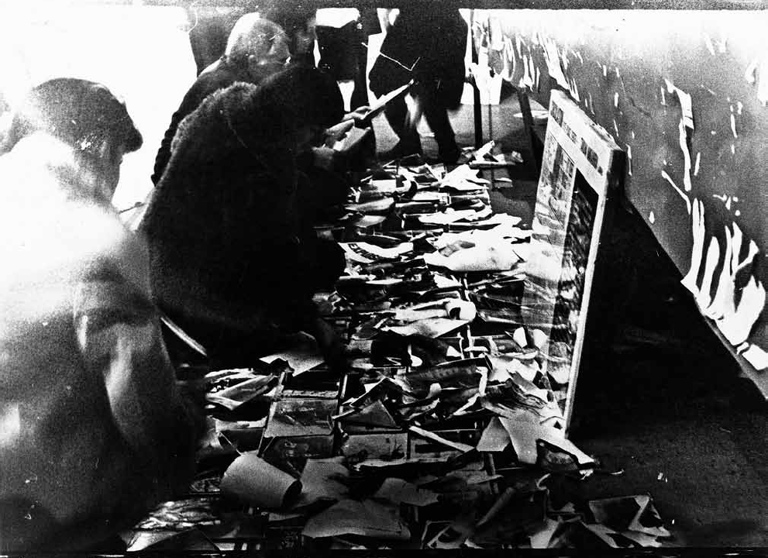

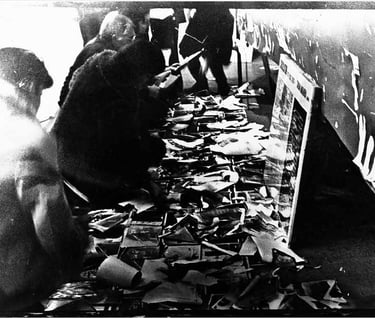

Held from September 24th to November 1st of 1971, the Seventh Paris Biennale took place during Nakahira’s desperate search for a new “language” between his realization of failure in 1970 and his total rejection of earlier work in 1973.4 Drawing heavily from Walter Benjamin’s “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, Nakahira attempted to challenge the values of artistic exhibition and the ritual of reproduction by producing and exhibiting nearly 1500 photographs in a week’s time in a piece entitled Circulation: Date, Place, Events. Feeling that it was “meaningless to try and force photography into a reductive framework of an ‘individual’ work”5 , Nakahira attempted to exhibit Paris as he lived it. Reminiscent of a Baudelairean flâneur, Nakahira captured material fragments of mundane Parisian reality, photographing everything from his empty hotel room, to busy streets and dilapidated metro signage. Structuring his production around a 24-hour cycle, Nakahira photographed, developed, and exhibited his work in the same day, often hanging upwards of 200 still-wet photographic prints for display. As the Biennale continued, so did Nakahira’s performance.

Fig. 1 and 2 display the chaotic nature of Nakahira’s Circulation: Date, Place, Events. Photographic prints, hastily hung, curl into themselves. Fig. 2 displays the daily aftermath, revealing Nakahira’s almost tortuous pursuit of continuous renewal. Violently pulled from their exhibition space and redistributed daily, Nakahira’s photographs seem to embody the disposability of reproduction. Through cyclical creation and destruction, Nakahira mirrors both the ever-shifting society around him and the trappings of repetitious history. His treatment of his own work in Circulation: Date, Place, Events encapsulates his continuous self-critique as a photographer, forever disposing and reconfiguring a political “language”. Nakahira describes his photographic process as an extension of lived process, “Yet, to live day after day, is this not to continue to represent and realize our selves as new selves every day? At the very least, we can be sure that this process of expression and expressing that is to create one’s self anew each day.”6 To Nakahira, the political is personal, and the photograph’s proliferation speaks to both.

In regards to the individual images, they do not appear drastically different than his previous works. High-contrast, black and white, blurry images continue to dominate Nakahira’s oeuvre. Emphasizing his obsession with the specific qualities of photography and collapsing the artistic photograph with the unencumbered snapshot, Nakahira included near-duplicates. Seemingly taken in succession, each work juxtaposes and emphasizes the temporality and unique quality of the other without making a clear break. It seems, thousands of miles from Japan, the photographer produces the same images in Paris.

Yet, Nakahira writes of his experience at the Biennale, “For me, writing about photography until now has been like the use of auxiliary lines in geometry. . . Now, as a result of this project, I can feel that the things that I say and things that I do are beginning to agree with one another for the first time.”7 Nakahira himself seemed to see a direct shift in his oeuvre during this exhibition: a shift linked to the performative act of his photographic production. In an essay written after-the-fact entitled “The Exhaustion of Contemporary Art: My Participation in the Seventh Paris Biennale”, Nakahira gives insight to the context of Circulation: Date, Place, Events. Looking back on the Biennale, Nakahira describes the paradox of a “Biennale which sought to create a venue for the free expression of free artists in the avante-garde of every nation” in the same city where two paintings by Lucien Mathelin were taken down in a “blatant case of censorship.”8 Here, Nakahira seemed to recognize that the paradoxical institutionalization of the “avante-garde” was not simply a Japanese trend, but an international one. It seems, thousands of miles from Japan, the photographer encounters the same images in Paris. Nakahira’s rejection of the institutionalization of the new “new” left in the failed protests against the 1970 renewal of the United States-Japan Security Treat continued into his rejection of the French Communist Parties’ “blatant” censorship during the Biennale. Nakahira, finally reconciling “the things that [he says] and the things that [he does]” left the Biennale two days early.