Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Dubuffet

Reeling in the destruction of war torn Europe, Jean Dubuffet’s Volonté de Puissance is a socio-political metaphor of the mentality of Europe after WWII that calls for a spiritual and intellectual cleansing of humankind’s collective soul. To do so, Dubuffet argues that one cannot simply subvert or do away with old structures and philosophies entirely, but that one must instead gather what metaphysical rubble there may be left over, and arrange it so one can cope more aptly with modernity.

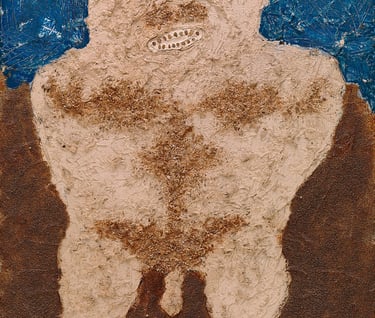

The European mentality in the years following the war is seen throughout Dubuffet’s piece: from the figure’s bound or amputated arms, to the crazed look in his eyes—even his nudity alludes to the psychodrama being played out in the minds of Europeans. The bound or dismembered arms depict a pervasive helplessness in the situation. How does one cope with the utter annihilation of the countryside? The city? Especially, how can one cope with such cataclysmic destruction when one is utterly powerless? When the power to wage war is in the hands of so few, as it was at this time, the individual is left psychically dismembered. Even in a democratic state, one feels the brunt of this disenfranchising structure, leaving one asking “Why?” His eyes and mouth are agape, seemingly in abject terror and awe at the sight of mankind’s so potent drive to self-destruction.

More importantly than this "why?" is the question of "what?"—what motivated Adolf Hitler and his Nazi regime to wage war on the modern world? Perhaps the title gives some clue. Translated, it means will to power. This concept of will translating into power is central to the Nietzschean philosophy perhaps incorrectly adopted by Hitler. Rather than adopt Nietzsche’s agnostic or atheistic views, Hitler instead twisted them to serve his own purpose in vilifying the Jews.

With that, the most obvious reading sees this painting as a critique of the guiding philosophies that led Europe to ruin. However, when one takes into account Dubuffet’s own principle of “rehabilitating the dirt,” it seems less likely that he is decrying Nietzsche, but instead championing his work in their true forms. Rather than do away with this piece of cultural heritage, Dubuffet demands that society refurbish it, taking the parts that still work and leaving the broken scrap behind.

Volonté de Puissance offers its viewer a complex perspective on the mentality of a Europe in ruins. It offers insight not only into the functions which led the continent to its ruin, but also to the philosophical and psychological pressures which led to the explosion of violence. Though it appears childish, Dubuffet presents his viewer and critic with multiple layers of meaning and readings. Of these, the title is most vague; is it because of the will to power that Europe lay in ruins, or is Dubuffet saying that it is this will that can lead people to a new tomorrow?