Kienholz’s ‘Five Car Stud’ at LACMA

Evan Moffitt

1/6/2012

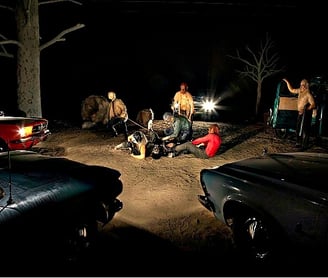

Iconic LA assemblage/installation artist Ed Kienholz’s piece, Five Car Stud (1969-72), is currently on veiw at LACMA after spending forty years in a Japanese storage unit. One of Kienholz’s most controversial works, Five Car Stud is an installation reflecting on the horrific violence inflicted on interracial couples in the era of its creation. Four cars with blaring headlights brighten up a scene of white men in rubber masks castrating a black figure, who writhes in pain on a dirt floor. In the fifth car, an old pickup truck, the victim’s wife buries her face in her hands, unable to face her husband’s pain and unable to save him from a brutal beating. Kienholz, who began his work making full-room installations in which he placed many of his assemblage combines, composes every detail of the scene—the padded dirt floor, the hunched figures and their rubber masks, and the twisted trees that shadow the scene. Installed in a dark room, you approach the installation as if stepping out under the night sky, to a roadside somewhere in the South. A car radio hums in the background, providing eerie elevator music where one would expect screams of pain.

Five Car Stud was understandably controversial when it was created, casting light (both figurative and literal) on the horror of racial violence. By spotlighting the castration, Kienholz creates a spectacle of the tragedy, in which the viewer becomes an audience to mutilation. Some visitors cry; others laugh uncomfortably. The victim’s face, the only visible one in the scene, looks strangely infantile. Sculpted from resin, it is dehumanizing, making him look like a baby rather than a man in pain. At a recent Getty talk, artist Betye Saar criticized the piece for making a painful and sensitive experience of African Americans into a spectacle. Saar’s criticism is warranted, but she ignores that any art which evokes challenging history serves to remind us of what we must prevent from happening again. Even now, when violence against interracial couples has almost disappeared, the piece retains currency for its historical value. Forcing museum-goers to witness a horror they’d rather ignore, Kienholz has created a permanent reminder of a dark chapter in American history.